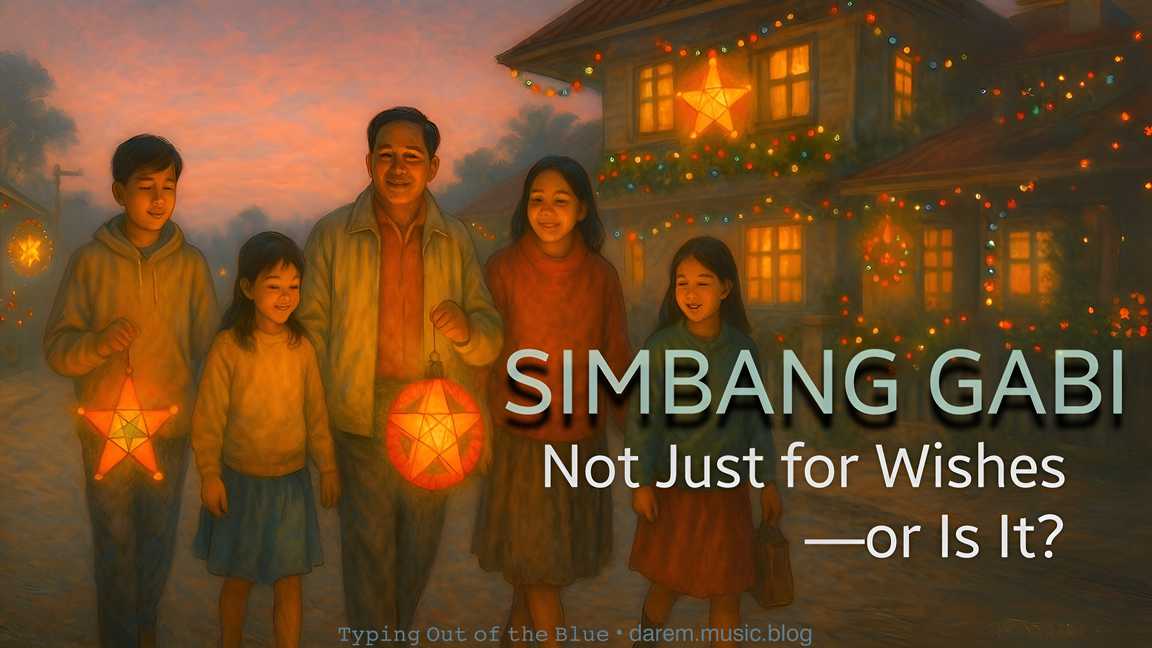

Simbang Gabi is about preparation.

For nine days, people wake up early while everything is still quiet. It slows you down before Christmas arrives.

Christmas is about the coming of Jesus. Simbang Gabi prepares the heart for that moment. It teaches patience, presence, and attention.

In another way, Simbang Gabi is also a countdown to Noche Buena. Not to the food, but to being together.

Most days, families are incomplete. Work, school, and daily schedules pull people in different directions. Meals are rushed or taken separately. This has become normal.

Noche Buena is different. At midnight, families try to gather at one table, even if only once in the year. The food is not the focus. It represents the blessings received through shared effort and sacrifice.

What matters is that people are present. Together. Thankful.

Simbang Gabi leads to that moment. It reminds us to prepare not just the home, but relationships.

It is not about getting what we want, but about being thankful for what we have.

⌨ ᴛʸᵖⁱⁿᵍ ᴏᵘᵗ ᵒᶠ ᵗʰᵉ ʙˡᵘᵉ ᵈᵃʳᵉᵐ ᵐᵘˢⁱᶜ ᵇˡᵒᵍ

Out this season on Bandcamp.