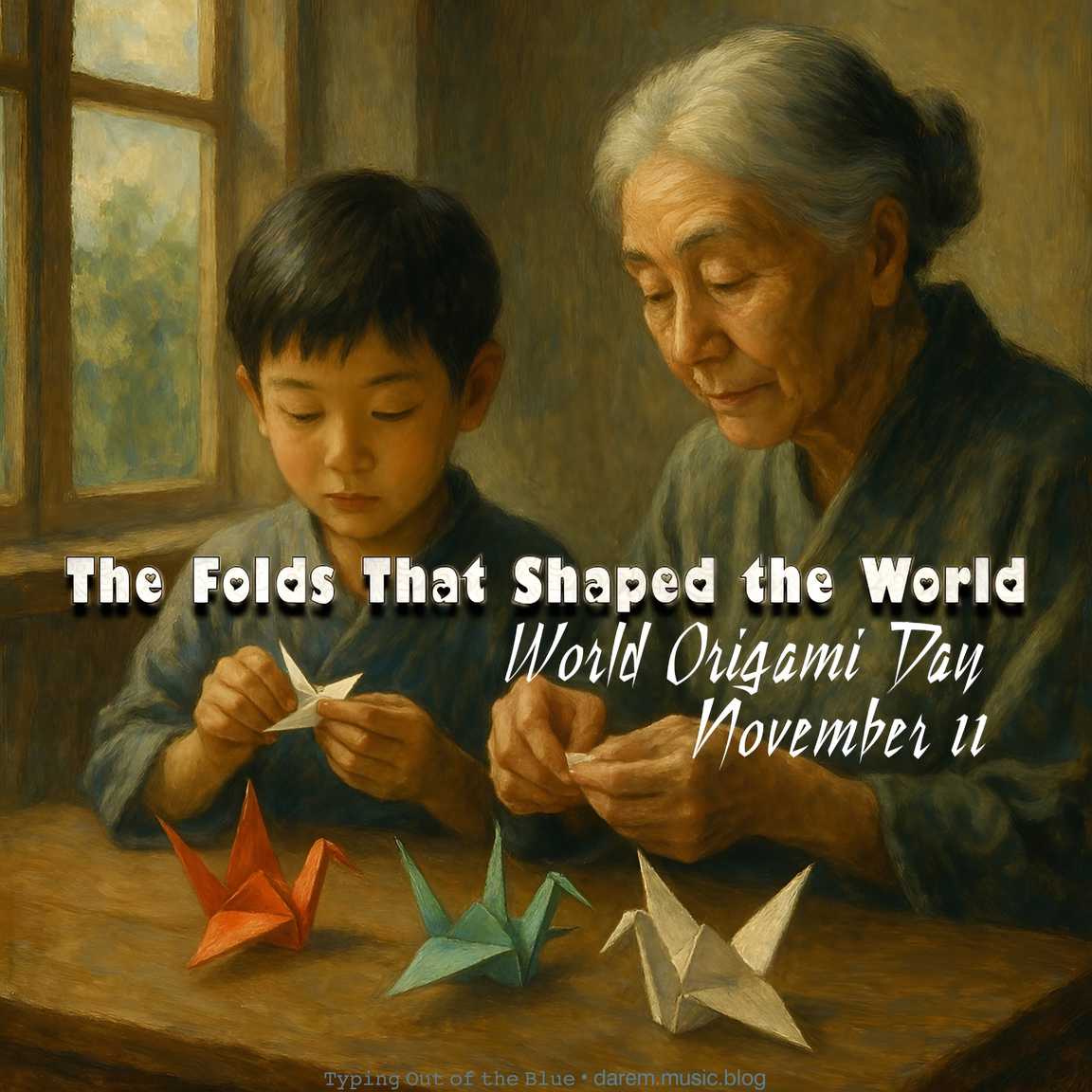

From sacred rituals to modern design, origami proves that patience and creativity can turn the simplest paper into art.

World Origami Day • November 11

Origami began more than a thousand years ago in Japan, back when paper itself was rare and sacred. People used folded paper in Shinto rituals—to wrap offerings and symbolize purity.

Shinto—Japan’s ancient belief system—centers on kami, or spirits that live in nature, people, and everyday things. It values purity, gratitude, and harmony with the natural world. That’s why even paper, when folded with care, was seen as something spiritual.

As paper became more common, origami evolved into decoration and art, spreading through families, temples, and schools. It flourished during the Edo period (1603–1868), an era of peace and cultural growth when Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa shoguns. Life slowed down, creativity thrived, and origami became a quiet pastime that taught patience and precision. Every fold carried meaning—the crane for peace, the frog for luck, the butterfly for love.

Then came Lillian Oppenheimer, the woman who introduced origami to the Western world in the 1950s. She founded the Origami Center of America and worked with Japanese origami masters like Akira Yoshizawa, who created the modern style of folding and invented the symbols used in origami books today. Because of them, folding became not just a cultural practice but a bridge between worlds.

Today, origami’s influence goes far beyond art. Engineers use folding principles for space telescopes, airbags, and medical tools. Artists use it for massive installations. Teachers use it to train focus and patience. And people still fold cranes—not for skill, but for peace.

Origami’s message hasn’t changed through centuries: even something fragile can hold infinite possibilities when handled with care.

⌨ ᴛʸᵖⁱⁿᵍ ᴏᵘᵗ ᵒᶠ ᵗʰᵉ ʙˡᵘᵉ ᵈᵃʳᵉᵐ ᵐᵘˢⁱᶜ ᵇˡᵒᵍ