When Bishop Anthony Mary Claret arrived in Santiago de Cuba in 1851, the diocese was almost forgotten. Churches stood quiet, priests were untrained, and the poor had no one to speak for them.

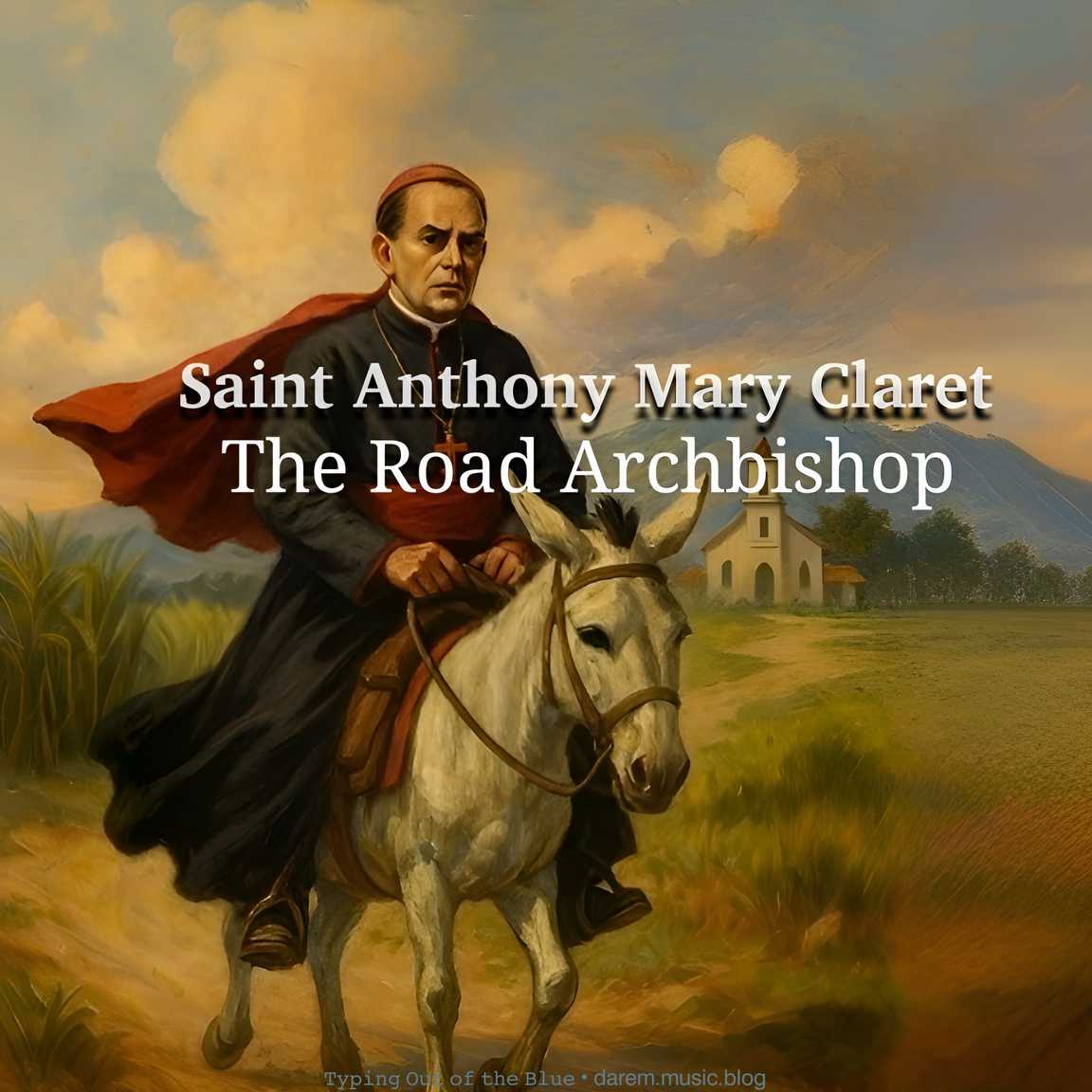

He had been appointed Archbishop of Santiago de Cuba the year before, in 1850, and soon began the work himself. He packed a few things and set out—on foot, horseback, or mule—crossing rivers, forests, and dusty plains to reach people no archbishop had ever visited. Historical accounts say he made several full pastoral journeys, visiting nearly all the parishes in his vast diocese.

He preached under trees and in open fields, sometimes beside sugarcane plantations where slaves labored. He baptized, married couples, and taught the young to read. He helped farmers improve their harvests and encouraged cooperatives so families could save money and avoid debt.

When an assassin once attacked him during Mass, the knife cut his cheek. He stopped the bleeding, finished the Mass, and later visited the man in prison—to forgive him.

He lived what he preached. His cassock was always dusty, his shoes worn thin. Historical records of the Claretians describe him as tireless and humble. He is attributed to have said,

“If I can prevent one sin, if I can bring one soul closer to God, then my life is not wasted.”

He used every talent and every chance for the good of others—proof that holiness isn’t about comfort. It’s about moving, walking, doing—until love itself becomes the road.

And that road, marked by dust and forgiveness, was the same path walked by Saint Anthony Mary Claret.

⌨ ᴛʸᵖⁱⁿᵍ ᴏᵘᵗ ᵒᶠ ᵗʰᵉ ʙˡᵘᵉ ᵈᵃʳᵉᵐ ᵐᵘˢⁱᶜ ᵇˡᵒᵍ

Listen on Apple Music, Apple Music Classical, and YouTube Music